“Droney” by Tom Tomorrow.

Last August, before domestic drones had become a concern worthy of a 13-hour Senate filibuster, I found myself inside a stretch limousine with a bunch of engineering students. We were on a rural highway in eastern North Dakota, rolling past bales of hay and soybean fields, the limo’s mirrored bar set with a row of empty champagne glasses. No one paid attention to them. Instead, the student engineers were deep in a marathon conversation about flying robots.

We had just come from Grand Forks, where they had competed in the granddaddy of all drone-building competitions. Now we were en route to the afterparty, which sadly was not a bacchanal. The first stop was a hop across the state border to Thief River Falls, Minnesota, for a tour of the headquarters of Digi-Key, an online purveyor of drone parts and other electronic innards. Then it was back to Grand Forks for some ribs.

Sitting next to me on the leather limo bench was Ryan Skeele, a willowy, thick-eyebrowed young man who goes by the nickname “Skeeler.” He’s a mechanical engineering major at Oregon State University, and at the time of our limo ride he was 21 years old — exactly the number of years that had passed since the first appearance of the drone-building contest, which is officially known as the International Aerial Robotics Competition (IARC). The contest encourages the current boom in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), a term organizers much prefer to “drones.”

In its early years, the IARC was little more than a showcase for glorified radio-controlled helicopters. Now, thanks to technological advances spurred in part by the booming smartphone market, the event draws students toting small quadcopters with remarkable capabilities. These drones are powered by the same kind of lithium-ion batteries used in an iPhone, and are aided in flight by miniaturized, inexpensive accelerometers and gyroscopes made possible by mass production of a billion mobile devices.

Anyone can buy a mass-manufactured version of these flying machines; an off-the-shelf model called the Parrot AR.Drone sells online for around $300 and is controlled using a mobile app on an iOS or Android device. And with the right amount of engineering know-how, as the students at the competition had just demonstrated, a device like the Parrot can be transformed into a flying robot capable of buzzing autonomously through the interior of, say, an intelligence agency compound like the one mocked up for this contest. The compound housed a coveted flash drive that, if found and extracted, would earn a $30,000 prize from the leading drone industry advocacy and lobbying group, the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International.

As the limo headed across the Red River of the North toward Digi-Key, Skeeler told me that Americans worry way too much about drones. He’d said something similar during the competition, telling me that people have become more afraid of invasions of their privacy because of the scary depiction of drones in TV shows and movies.

His own team’s experience at the competition did seem to support the notion that easy-to-purchase drone technology is not at the run-and-hide stage just yet. The Oregon State quadrotor drone, assembled in a basement laboratory at the school’s Corvallis campus, had proved unable to fly effectively due to glitches in its communication system, and Skeeler and his two teammates were forced to withdraw.

The contest winner, however, offered a much different sense of our proximity to a sky crowded with citizen-owned drones able to conduct all sorts of missions, legal and otherwise. Built by students at the University of Michigan, this quadrotor arrived in Grand Forks inside four large, black suitcases, the lids of which glowed blue with the logo of the Michigan Autonomous Aerial Vehicles club. Nestled in the padded interiors of these cases were four copies of a candelabra-shaped drone made out of hollow carbon tubing milled in that school’s labs.

At first, the Michigan design bobbed and weaved down the hallway of the mock spy compound, looking like some tiny drunk careening home at 3 a.m. But this was just a sign that its radar and artificial intelligence systems were overreacting to obstacles the machine spotted. Once recalibrated, the Michigan drone successfully flew on its own through a window at the mock compound, set in the fictional country of “Nari” (Iran spelled backwards). It then easily navigated and mapped the base’s interior, flew back out through the same window it had entered, and set down not far from the spot where it had taken off.

The Michigan drone wasn’t able to steal the flash drive, which meant the $30,000 kitty was unclaimed and will grow to $40,000 for the next round later in 2013. But the vehicle’s prolonged casing of the joint followed by a successful escape was a better performance than any other student drone had ever achieved in the contest. The audience, which included representatives from defense contractor Northrop Grumman, cheered wildly. (The company, a founding sponsor of AUVSI, has a presence in North Dakota to support drones at the nearby airbase.)

While watching this unfold on a covered portion of the University of North Dakota basketball court, I asked Aaron Kahn, an engineer who designs drones at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, about just how far this Michigan drone was from the capabilities of current small military unmanned aircraft. Kahn, who used to compete in the event and now helps organize it, emphasized he was speaking as a private individual and not on behalf of the lab. He said he didn’t have specific knowledge of what’s actually in the field — he wouldn’t have been able to say anything at all if he had. But, he would go so far as to say that the competition drones were probably “not far” from the what small military drones could accomplish, as well as being “state of the art” for civilian equipment.

This seems cause for some concern. While military drones have become quite controversial, especially when used to target American citizens overseas, that use is by definition tightly controlled and limited to an extremely small segment of the world’s population. The sense of limited danger changes significantly when one considers that the Michigan team, acting as private individuals, built their drone close to military caliber using materials available to any U.S. citizen — many of those parts purchased online via Digi-Key, a team sponsor.

It’s not a stretch to imagine that a few years down the road a device like the Michigan team’s drone will be sold as a shrinkwrapped item. That in turn makes this worth considering right now: What happens to our privacy and our safety when all Americans can, with a few clicks, purchase their own flying proxies to act out their wishes?

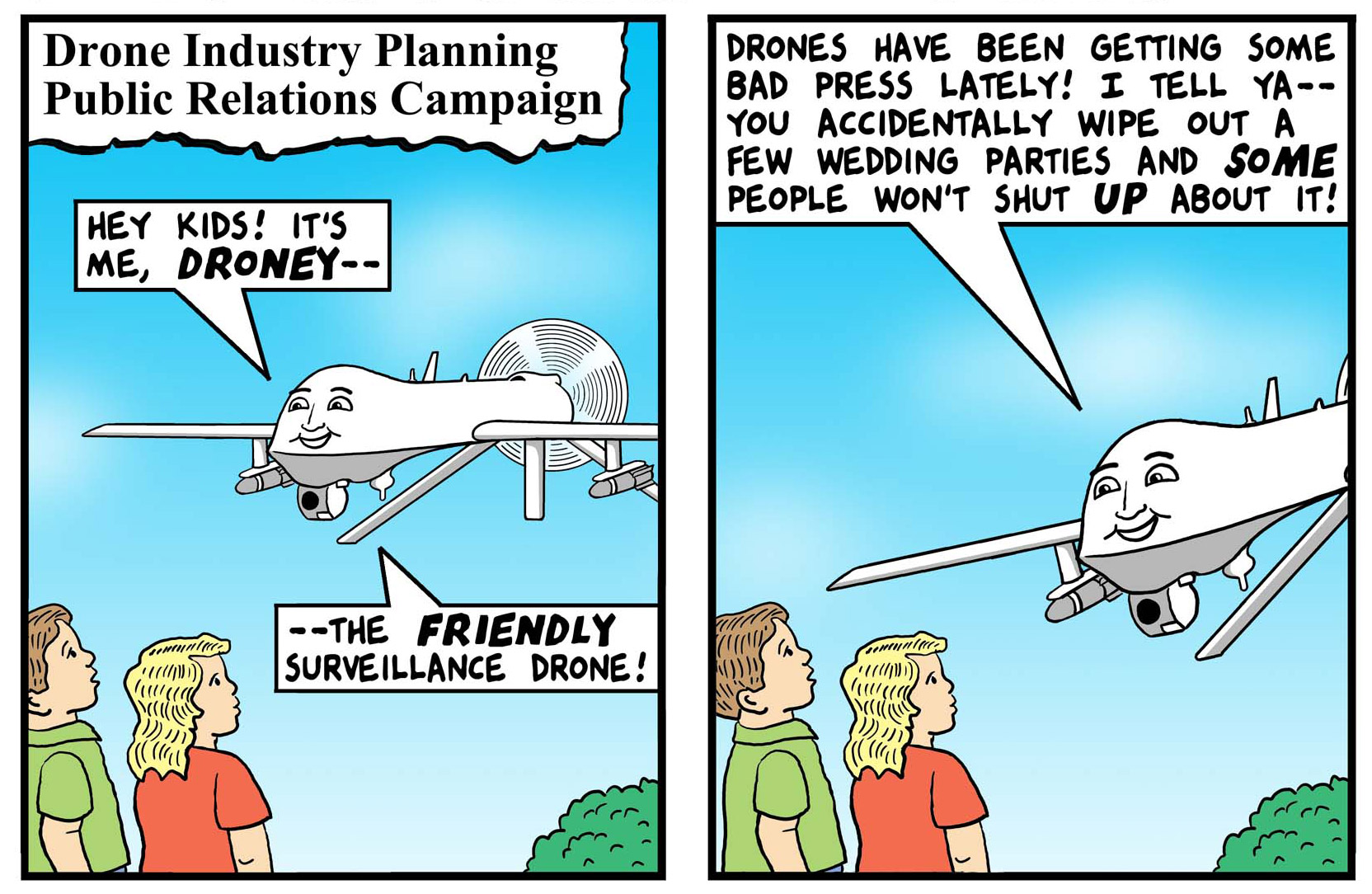

“Droney,” part 1 of 3, from This Modern World by Tom Tomorrow.

Hovering in regulatory limbo

Government agencies are not quite ready for this future. President Obama and Congress have ordered the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to come up with rules about how private citizens, companies, and government agencies can fly drones in the national airspace — but the agency has until 2015 to release those rules. Meanwhile, the reality is that all of these groups already fly drones in the national airspace.

To begin to address this, early last year the FAA announced plans to offer preliminary rules for users of small drones by December 2012. The agency also said it would choose test sites in six states to experiment with integrating drones into the nation’s skies. Then, without an explanation other than that it remains busy considering citizen feedback, the FAA delayed both the rule-making and picking the test sites.

For now, civilians have been told to use their off-the-shelf drones below 400 feet and within the operator’s line of sight. Drones may not be used for commercial purposes, which shelves projects like the Burrito Bomber. Also, police departments, universities, and media companies that want to play around with drones need special authorization from the FAA (which the agency has granted plenty of times).

Maintenance personnel check an MQ-9 Reaper drone before its surveillance flight near the Arizona-Mexico border on March 7, 2013. U.S. Customs and Border Protection flies the unarmed aircraft an average of 12 hours per day, piloted from the ground, searching for drug smugglers and immigrants crossing illegally from Mexico into the United States. Photo by John Moore/Getty Images.

And the government? It’s already using drones in the nation’s airspace for limited missions, like the unarmed Predators that take off from Grand Forks Air Force Base to monitor the northern border, a separate flock of Predators controlled from Texas that do the same for the southern border, and the Global Hawk surveillance drone that has helped NASA gather information on impending hurricanes. A United States Global Hawk was also used to help monitor the Fukushima nuclear complex in Japan after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

The government’s limited domestic use of drones has already led to dark fears of mission expansion — fears that someday drones may be turned against Americans in uncomfortable ways. Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has been one of the loudest in voicing these concerns. He used his 13-hour filibuster on March 6–7, which temporarily blocked a vote on the nomination of John Brennan as head of the CIA, to declare that the Obama administration had left the door open to tactical drone missions on American soil. In response, Attorney General Eric Holder wrote a letter to Paul stating his opinion that the president lacks authority “to use a weaponized drone to kill an American not engaged in combat on U.S. soil” — which is not a complete answer, but Paul accepted it.

More quietly, Representative Ed Markey (D-Mass.) has been pushing for legislation to make sure the average citizen’s privacy — and not just the average citizen’s safety — becomes a primary concern for the FAA as the agency seeks to balance drones and the public interest. At present, the FAA’s expertise is mainly in addressing safety concerns. But the Parrot AR.Drone comes mounted with two video cameras (one of them high-definition) that could easily be used to spy on one’s neighbor. Markey has called the FAA’s lack of attention to privacy concerns “a blind spot in its oversight of domestic drones.” (In February, when the FAA announced a public comment period on drones and privacy, Markey applauded.)

Even the ACLU finds itself in a pickle over how to proceed. The group says it wants to protect First Amendment rights related to newsgathering and protest marches that could be aided by civilian-owned drones, and Catherine Crump, an ACLU attorney working on drone issues, pointed out that some Occupy protesters in New York used a drone to stay a step ahead of the cops. But at the same time, Crump said that drones “raise substantial privacy concerns, particularly when they are used to observe activities in private spaces not normally in public view.”

Open skies

Adding further ambiguity to the airspace, legal scholars warn that the statutory sphere isn’t ready to handle drones, either. Take, for example, a frequently raised question: If a drone is hovering over my private property, do I have a right to shoot it out of the sky?

In this property-rights-obsessed nation, it turns out you actually don’t have a clear right to shoot down a drone hovering low over your backyard unless it’s putting you in imminent physical danger.

“You have to acknowledge in this day and age that stuff flies over your house,” Ryan Calo, a professor at the University of Washington who specializes in robotics and the law, told me. That puts him at odds with conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer, who voiced a more typical reaction on Fox News last year: “The first guy who uses a Second Amendment weapon to bring a drone down that’s been hovering over his house is going to be a folk hero in this country.”

Calo notes that airplanes can already fly over anyone’s house without permission. No one balks at that, and if the autopilot is engaged on a commercial or private aircraft, it is essentially a drone. Police helicopters may fly over the average citizen’s house, too. “There are lots of doctrines that say you can look into someone’s backyard from the air,” Calo said. Even if you avoided Krauthammer’s recommendation of using a gun and merely lobbed a tennis racquet at the neighbor kid’s prying Parrot, you could be in trouble for unjustly taking it out; Calo said that the kid’s parents might be able to sue you for damages to his flying property.

Clearly the law will have to adapt to the rise of the domestic drone. It may also need to anticipate it, which could be even trickier. Calo points out that the U.S. Supreme Court recently decided two cases related to what police officers should be allowed to do with a now-standard law enforcement tool: the contraband-sniffing dog. He’s been watching them closely because of a technology that’s coming: police drones that can “sniff” the air for traces of chemicals associated with illegal drugs, and even search for hidden weapons under a person’s clothing using non-ionizing radiation.

While the high court’s rulings in the police dog cases made it less likely that authorities will fly a contraband-sniffing drone up to a person’s front door without a warrant, Calo said the justices left unanswered the question of whether police can fly a sniffer drone warrant-free over someone’s property.

Others have warned that we should soon expect drones equipped with facial recognition technology and biometric data gathering capabilities. In a radio interview on March 22, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg called this a “scary” prospect that’s coming whether we like it or not. “We’re going into a different world, uncharted,” Bloomberg said. “We’re going to have more visibility and less privacy. I don’t see how you stop that.”

Calo thinks it should be possible to develop sensible drone laws and regulations, but he also worries about what happens if a determined, regulation-ignoring citizen, in some futuristic variation on Adam Lanza’s December killing spree in Newtown, mounts a weapon on a drone, flies it into a crowd, and opens fire.

He wonders, too, whether humans would feel the need to punish the drone as well in that instance, perhaps by destroying it publicly. He’s seen research that suggests the more anthropomorphized a robot is in its design, the more blame people tend to place on the machine rather than its operator or creator.

“The technology is going to allow drones to become cheap and easy and ubiquitous,” said Chris Anderson, former editor in chief of Wired magazine, and now the chief executive of 3D Robotics, a manufacturer of drone kits and fully assembled units. The company grew out of a Web community, DIYDrones.com, that Anderson started as a part-time hobby. It now has annual sales in the millions. “You know, tens of dollars, the size of your hand, and you just push a button and you do something.”

For the overwhelming majority of Americans, that something will probably involve mundane domestic tasks like seeing the kids off to the school bus. But what about when a person’s airborne avatar gets enlisted to help out with a common impulse like revenge?

Continue to Part 2.

Illustration and cartoon by Tom Tomorrow.

Eli Sanders is an associate editor at The Stranger and the winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing.