Shortly after 8 a.m. on June 19, 1988, in Block Canyon, an area of the Atlantic Ocean 100 miles off the coast of Rhode Island, I felt, then saw, my first shark.

For two days, the crews onboard the sloop swapped turns: one kept busy dropping baited handlines into a chum slick while the other crew rested. I was becoming accustomed to sleeping in a coffin-sized space for four-hour stretches on a steeply canted sailing vessel. But the sudden pounding on the wall of my berth — this urgent, erratic thumping coming from the ocean side of the hull — felt like being punched through a table. It meant the other watch had pulled in a shark. No matter that I had been awake since 3 a.m., chumming with no luck throughout the final portion of the late watch; I lurched from the bunk and raced on deck.

This first shark was one of seven hauled in that morning. By the project’s end I would witness or help bring up some 500 more. This shark’s specificity has fused with the others, but because I documented the occasion in an orange notebook that I still possess, I know that I felt wonder: My first shark…They are beautiful creatures. Made out of sleek steel greys and iron metallic blues and have sheer white bellies. Amazing.

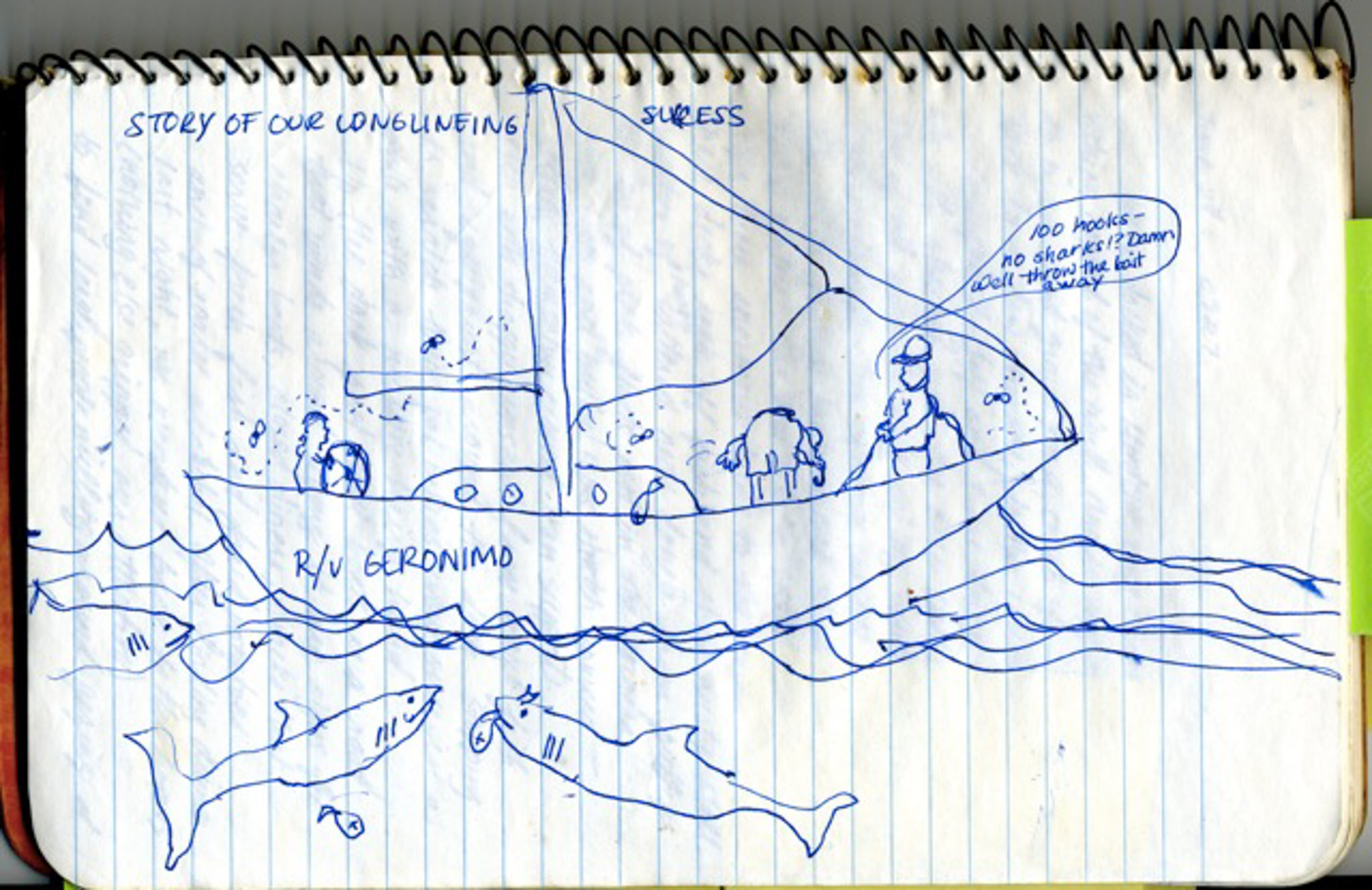

I spent a month of my 16th summer tagging blue sharks for the United States National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) on a 69-foot research vessel, the Geronimo, owned by St. George’s School in Rhode Island. Far from parties and boys and the steering wheel of a car, I drifted over the continental shelf with Captain Connett and his son, Stevie; Lisa Toland, my English teacher, the person who convinced me to enroll; and five other students. We whiled away the days attracting sharks thusly:

That’s right, you take a stiff salted mackerel and push it into the opening [of the meat grinder] while somebody cranks the handle. About halfway through, its mushy stomach rips and grisly slimy intestines and mush slops out.

This produced ooze for the chum slick, which we ladled, hour after hour, into the ocean that occupied the horizon around us. Then we baited longlines or handlines and hung them from the boat.

As participants of the NMFS cooperative shark tagging project, all of our waking moments that month were consumed with finding and tagging the 580 sharks we attracted. In the ship’s log we noted their species (blue sharks were by far the most common), length (they ranged from a dainty three feet to an intimidating eight feet), gender (males have double penises, called “claspers,” that resemble the long fingers of a white glove), and any markings, gashes, or scars (females often had “mating scars”).

Then one of us would tackle the long pole with a tiny numbered metal tag at the tip and spear the shark at the base of its dorsal fin, jabbing that tag in for perpetuity. My favorite job was kneeling on the deck, leaning toward the fish to clip the monofilament line from the swallowed hook as close to the shark’s mouth as I dared, then watching as it swished off into the ocean.

Years later, I wondered what became of these close encounters.

Bait and switch

To find out the fates of our tagged sharks, I contacted the St. George’s School archivist, Val Simpson, who mailed me copies of the shark log from the summer of 1988. The tag numbers listed therein (many written in my best teenage penmanship) allowed Nancy Kohler, head of the Apex Predators Program at the National Marine Fisheries Service, to produce a sheet of data that detailed recaptures. Cross-referencing this with the orange notebook I kept — chronicling the sharks we met, if briefly, just over a quarter of a century ago — 26 of our recaptures splashed back to life.

For example, two of the seven sharks that were tagged the morning of my first shark, June 19, were recovered. One, #126129, a four-and-a-half-foot male, was found by a Canadian fishing vessel two months later, 267 nautical miles southeast. The other “beautiful creature” from that first morning, #126131, a six-foot male, hooked just a few minutes later, was recaptured by sport fishermen four years later and 68 miles east.

On June 28, the 10th day of the trip, we were drifting 38 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard when we began a six-hour tagging bender. By early afternoon we had tagged more sharks than in all the previous days combined. Among those was a four-foot female. She chomped our mackerel-baited hook and began to swim away. As she retreated, the monofilament, the other end of which was connected to a rope-like line I was holding, began skidding through my waffle-gridded mitts.

The tagger’s trick I learned is to let the shark think she can take the bait and dash away by letting the line pay out loosely through your palms, and then, after she has had her spree, you grip and the “discussion” begins — a discussion you will dominate because of the hook. You tug back and she fights. You let her struggle, paying out more line in deference; there are two miles of line in the barrel on deck beside you. When her vigor flags, you assert, hand over hand, drawing her back.

The conflict lasts: “I am going,” she communicates with a strong tug; “No, you’re not,” your pull answers back, until the shark’s energy is spent and you pull her alongside the boat, where she receives inspection — no mating scars, the tag #126234 — and, at last, release. She is noted in the ship’s log along with 58 others tagged that day. Fare well.

However, #126234 was reeled in by a sports fisherman just four months later, the day before Halloween, 292 nautical miles west of our encounter. According to the NMFS data, she was discovered off the Virginia coast, 10 miles north of Norfolk Canyon, and 10 centimeters longer than when we’d met her, though ours was an estimate.

Almost one full year after we tagged #126234, she bit another hook and surfaced yet again, this time in late June of 1989, 21 miles southeast of Fire Island Inlet, New York.

Thanks to her tag and the voluntary assistance of fishermen, #126234 provided a glimpse into the yearlong commute of a blue shark.

You’re it

By 1987, the year before I stepped aboard the Geronimo, John Casey, a fisheries biologist who had been studying shark populations for over 25 years, noted that 68,000 sharks had already been outfitted with little metal tags trailing from their dorsal fins, and of those, 2,400 had been recaptured. In addition to students and scientists, both commercial and sport fishermen had been voluntarily participating in the longstanding NMFS cooperative tagging program, creating a current of data that told the life histories of large Atlantic sharks.

Our work that summer would become just a drop in the ocean of the tagging program. Yet data derived from the ongoing project, the Geronimo taggers of years past, had helped inform Casey’s efforts to understand sharks’ diet, reproduction, age growth, and migrations. Any of our recaptured sharks would continue to further his and others’ understanding of the mysterious, often maligned fish.

My ongoing curiosity about sharks, more gawker than nature-wonk, stems directly from that summer and a connection abetted by more than just monofilament. For a month, I became a part of the marine environment, and my orange journal abounded with descriptions of it.

Observations:

Last night fog just cuddled the boat and I was soaked and cold to the bone on watch…we all amused ourselves setting the longline, watching the phosphorescence, playing games with squid until off the port side we saw dolphins surfacing. One dove entirely out of the water in an arabesque leap. It was amazing — imagine these sleek quiet creatures suddenly emerging from a foggy 4am sea.

And crankiness:

I got to cook again [rant about shipmates and unfair work distribution here] the boat is rolling and pitching to no end. Cooking dinner was hell — it’s bad enough trying to cook for nine people, but the stove was gimbaled, grease spattering and flying everywhere — it’s like trying to cook in an earthquake.

And descriptions of work:

So tired. 2300–0300 watch [11pm–3am]. Sea was like silky black ink …I chummed until my back ached. Ladling… minced mackerel into what seemed an empty ocean.

And discovery:

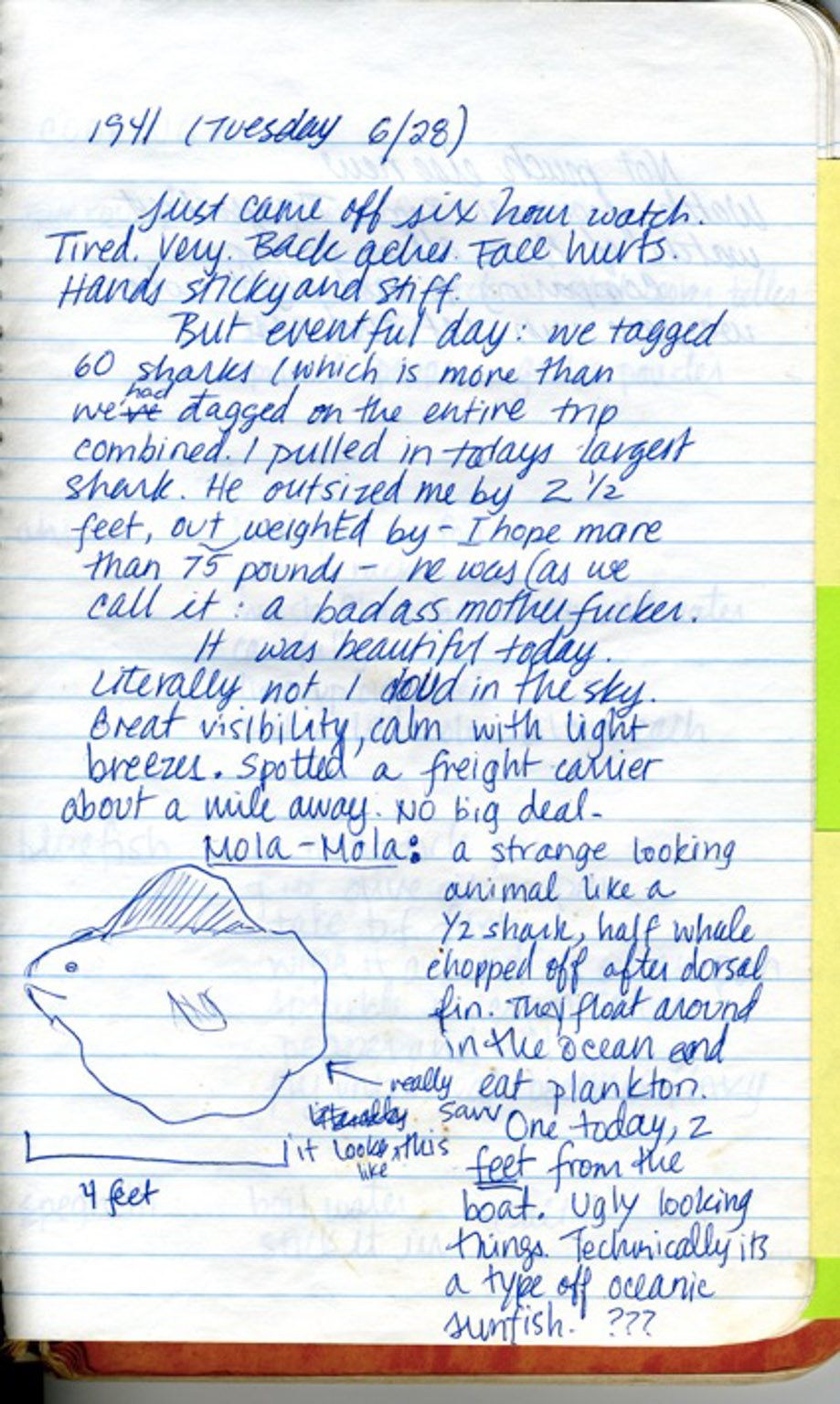

Mola Mola: a strange looking animal like a…half whale chopped off after the dorsal fin. They float around in the ocean and eat plankton. Saw one today two feet from the boat.

We pulled a 7½ foot Mako in. It was female, teeth pointing out of her mouth every which way like pins on a pincushion… Jaws material.

Tagged 4 basking sharks—which are 20–40 feet long and weigh on average two and a half tons, yet they manage to propel themselves out of the water in a mini arc. Their dorsal fin, which can be spotted on the surface of the water on a calm day, gives no indication that the beast below it could house a Toyota and a Jeep in its stomach.

Shark trek

Most of the 26 recaptured sharks were discovered in the same Atlantic neighborhood: from the waters off Cape Cod and south to the waters off Long Island. For five years following our voyage, they were found by private and commercial fishermen within a 500-mile radius from where we’d first met them.

Their range spanned in every direction. One was found 267 miles southeast, another 13 miles northwest, another 134 miles northwest, another 68 miles east. Most of our sharks were found close to home, relatively speaking — if an animal that has to move to survive can be said to have a home. However, three sharks were found thousands of miles away.

According to the Geronimo log, in early July we hung two handlines over the side of the ship, baited with bluefish scored off a sportfishing captain during a brief anchorage in Nantucket. On July 5, I recorded how we’d been chumming all night into the foggy morning, when an abrupt weather change swept the fog away. Over the next 24 hours we tagged 269 sharks. Yet for all our exertions, not one of the first 126 sharks we tagged during that spell ever revealed itself again.

But the 127th did. A male blue shark, he first distinguished himself in the log and memory by being attacked by a sea bird called a shearwater, which swooped in to nip, perhaps after the bait more than our catch. We hauled the 6-and-a-half-foot cartilaginous fish alongside the boat and jabbed in tag #126553.

He was later found both the farthest away and nearly the farthest number of days out from our logging location. Five years later, on January 20, 1993, he was caught on the longline of a Spanish commercial fishing boat 2,712 miles away, off Cape Verde near the west coast of Africa. A Spanish fisheries observer onboard documented his length as 240 centimeters (nearly eight feet).

Two other sharks we tagged that summer were also discovered far beyond the territory where we’d found them two years earlier. In 1990 these sharks were discovered by separate Spanish commercial fishing vessels: 1,380 miles and 1,684 miles away. They had made it halfway across the North Atlantic, east of the Azores.

Pilot fish

The practice of tagging marine animals to gather oceanographic information can be traced back to the 1930s, when a scientist, Per Scholander, attached a gauge to the fin of a whale to measure dive depth. Since the late 1980s, tagging technologies, now grouped together under the term biologging, have become ever more sophisticated. Tags relaying physical and biological data have been attached to a variety of marine life, and now these “research assistants” include mola molas, bluefin tuna, leatherback turtles (which carry a tag that looks like a backpack), green sturgeon, elephant seals, juvenile salmon, and salmon sharks, to name a few.

Our 4.5 percent recapture rate demonstrates the limiting factor of tagging: finding the animal again to retrieve the data. Now the ever more sophisticated equipment, including acoustic archival tags and satellite tags, has made yet another leap: autonomous underwater robots programmed to follow sharks with a transmitter tag. Independent efforts have been made by marine researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) in Cape Cod (paid for by the Discovery Channel, which wanted Great White footage) and a biologist-engineer team from California State University at Long Beach and Harvey Mudd College on the West Coast. (A group at the University of Delaware has performed similar tracking with a remote-controlled device.)

According to Marine biologist and shark expert, Greg Skomal, the WHOI robot has video capabilities which it uses as it receives signals from the shark’s externally attached transponder; the robot “navigates relative to where the shark is.” The Cal State team’s robot is designed to receive acoustic signals from a transmitter embedded in the shark’s dorsal fin and relay them back to a computer on land, informing scientists about the shark’s track.

This next-generation technology allows researchers a more intimate, if physically remote, understanding of a species’ life. But the robot will never look upon the sunrise with relief after a long night of chumming and appreciate that the sea looks like rippled tinfoil.

Current whereabouts

The lifespan of a blue shark is roughly 25 years; hence, I have probably outlasted not only the recaptures but all 580 of the sharks we tagged during the summer of 1988. As I re-read the final entry of my orange journal, it seems appropriate to note my own data: it’s 26 years later, I’m 400 miles northwest, and I am a full-grown female.

The orange journal concludes:

July 10, 1988 8:46pm

I just had dinner with the Connetts. F. and L. left this afternoon. B. did too. W. is spending the night at a friend’s house. So is J. And Lisa is not coming back either. So that leaves me…the last.

And indeed I am the last — that is, if I left at all. Captain Connett retired in 2001, and though the Geronimo sails with a new generation of students, their studies now focus mostly on sea turtles. My desk is covered in maps and spreadsheets and logs, as if, in the end, I had been tagged by all those sharks.

Photos courtesy St. George’s School. Notes by the author.

Julia Shipley is an independent journalist based in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. A frequent contributor to Yankee magazine and Seven Days, Burlington's independent weekly, her work has recently appeared in American Forests, Northern Woodlands, and the Burlington Free Press.