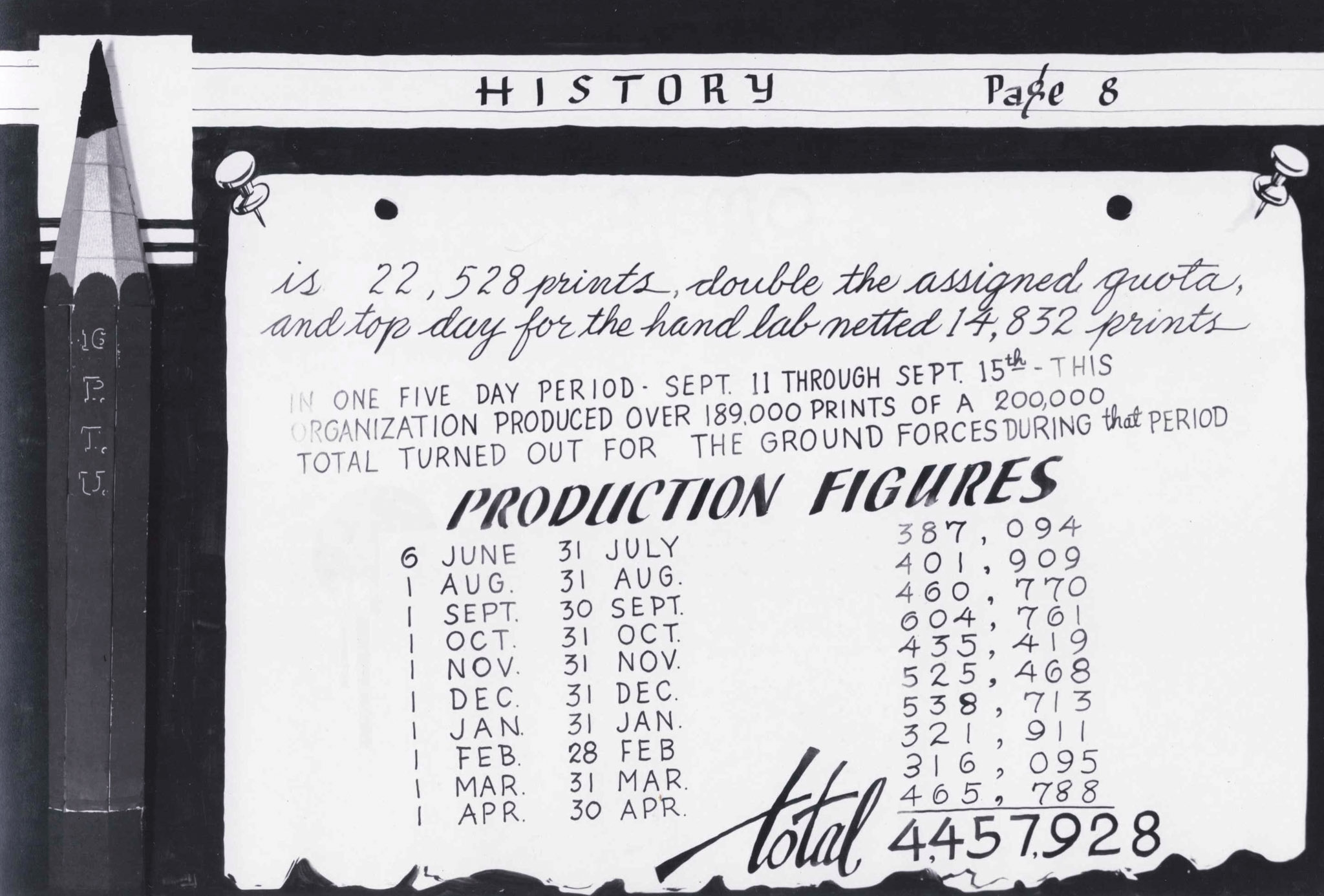

The number is impressive, and it’s precise: 4,457,928 photographic prints produced during an 11-month period. In a world of digital photography, that total might be met with a shrug. But the circumstances in which those 4.5 million prints were made transform a repetitive task (that at the time involved a darkroom and developing fluids) into something bathed in courage — a corny word, and an odd one until you know that the 11-month period ran from just after D-Day until April 30, 1945, and that the darkroom was in one of a small group of trailers rolling across World War II’s European Theater.

Spools of film were pulled from the hulls of airplanes just back from reconnaissance flights over Germany and rushed to mobile labs for quick processing. Troop movements, economic and military targets, and the success of bombing missions were all assessed by examining aerial reconnaissance photos.

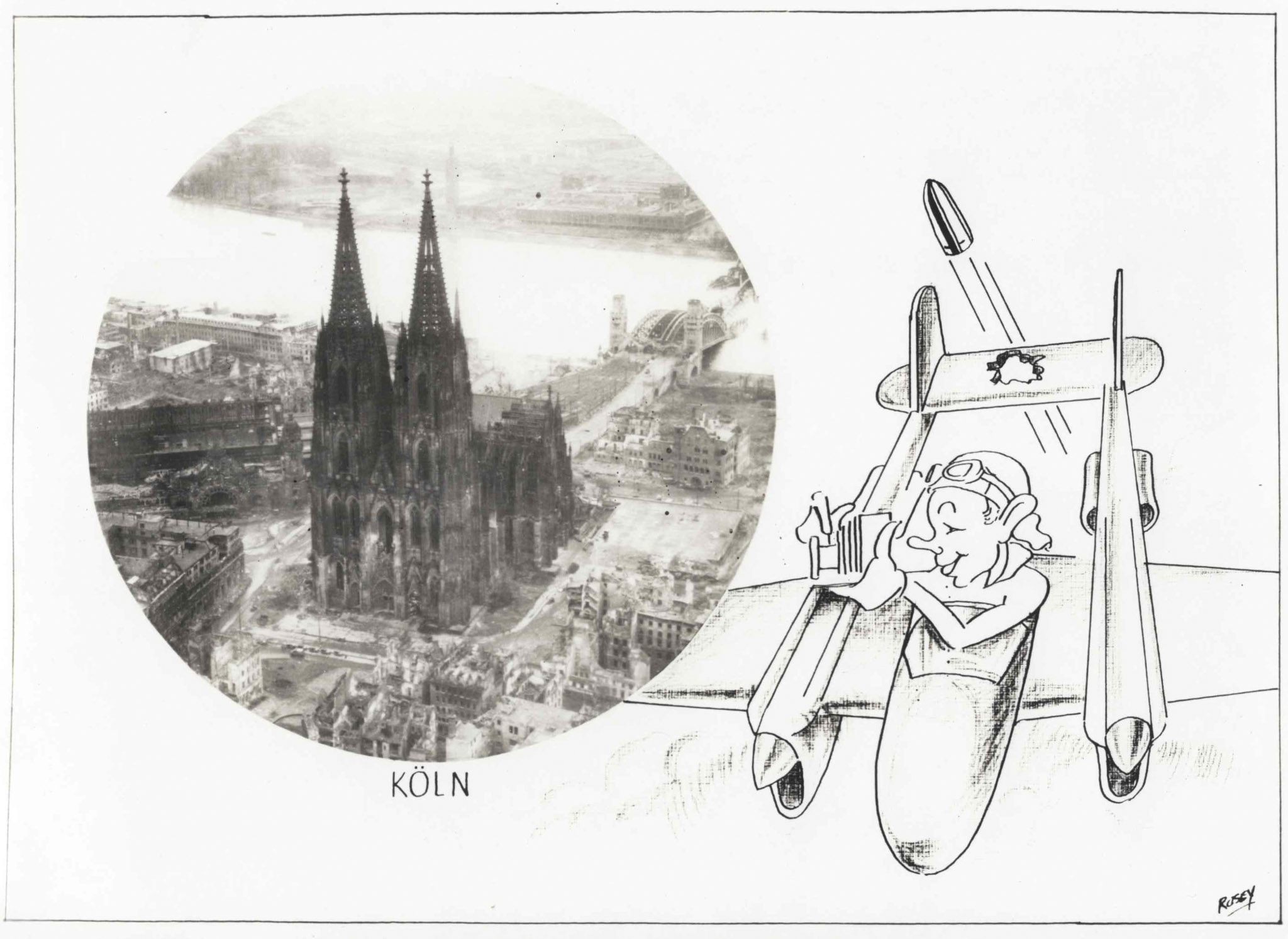

One of those World War II mobile labs was run by the US Army’s 16th Photographic Technical Unit, which was attached to an Air Force squadron. As a group they were expected to supply complete aerial photographic coverage of the First Army front to a depth of 10 miles behind enemy lines every day. The 16th Photo Tech first hunkered down in England before traveling to Normandy a few weeks after D-Day. At various times, it operated out of Le Moley, France; several locations in Belgium, including Gosselies, now the site of one of the largest Caterpillar plants in Europe; Voegelsang, a Hitler youth camp taken by the Americans; and multiple cities in Germany, including Limburg and Eschwege.

Most of this information I found in a sort of commemorative scrapbook, called Blue Train, that was given to the members of the 16th Photo Tech at the end of their service. It took me a long time to discover the meaning of the title. It seems the Americans learned much about aerial reconnaissance tactics from the British and even employed British-made processing equipment in the field. Units like the 16th Photo Tech were nicknamed “blue trains” because the British painted their photo lab trailers blue.

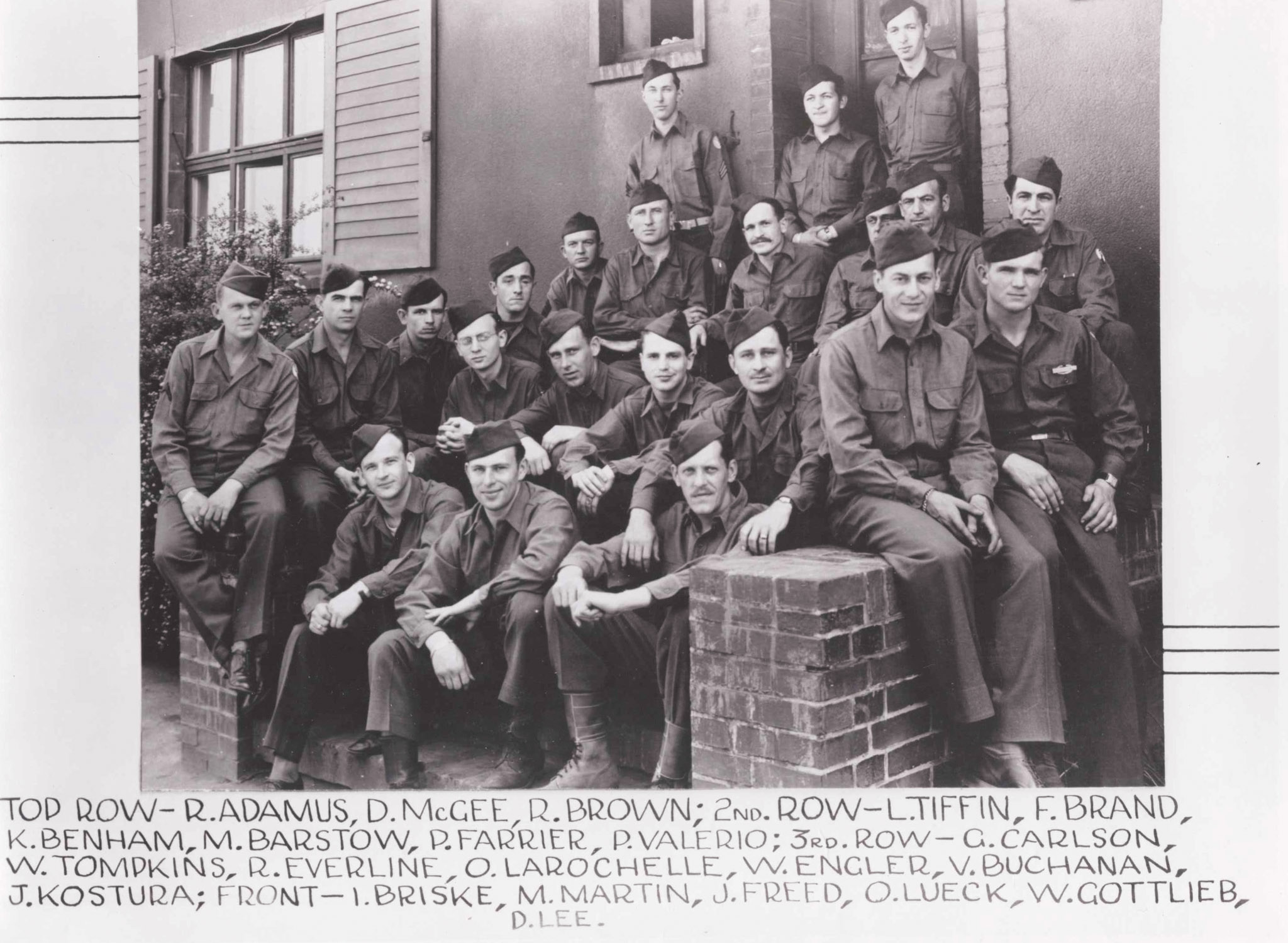

On the second page of Blue Train, the scrapbook is described as “an unofficial pictorial sketch of our activities in the E.T.O.” On page 32, a photo shows about two dozen members of the 16th Photo Tech posing for a group shot on a few low steps in front of a bland building. In the second row, with his hands clasped and, like all the other men, his cap tilted to the side, sits my father.

Tangled up in blue

After my father passed away in 2008, I acquired the Blue Train book, thinking I might like to research the unit’s path through Europe. But I managed to uncover very little information. When I did come across a mention in a book or Web site of, say, mobile photo processing labs or the specific Air Force squadron the 16th Photo Tech worked with, I felt I was wading into the murky waters of esoteric, jargon-filled military history — an official report or a dissertation rather than a story.

For example, I discovered the origin of the term blue train on a Web site devoted to the 33rd Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron of the US Army’s 9th Air Force. When I sent an email to the generic address listed on the site asking if anyone knew about the 16th Photo Tech, the response, which came from a man named Richard Faulkner, began with, “Blue Train is a name that resonates for many in the photo recon community who served in the ETO and a bit of a mystery to many. I have very limited knowledge of the unit.”

Faulkner later sent me excerpts from a 1945 publication called Reconnaissance in the Ninth Air Force, which went into numbing detail about organizational structure (“Each Group included a Photo Control Section to which the Photo Reproduction Unit and its associated Photo Intelligence Detachment [PID] belonged”) and the production capacities of the various processing machines.

The site Military History Online includes a long entry about World War II aerial reconnaissance, but its author knew nothing about the unit. “I wish I could offer some first-hand info on the 16th Photo Tech Unit,” he wrote in an email, “but I’m afraid I am drawing a blank.”

One mystery in particular about the 16th Photo Tech’s itinerary I was hoping to solve arose from a photo album my father had kept on a closet shelf next to Blue Train: its pages are filled with pictures of the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Yet there’s no mention in Blue Train of being at a concentration camp, even though the author, whoever he is, cheekily refers to how “our armies ground the master race myth of the Hitler-heilers into the same dust from which it rose.”

Blue Train does provide one particularly helpful element for those trying to dig up information about the unit: head shots of all the members of the 16th Photo Tech, captioned with each man’s name and hometown. A few years ago I set up a Web site about the 16th Photo Tech, with a page that listed all these names. Since then, every few months an email appears in my inbox from one of those men’s relatives who had come across the site.

Mother always talked about how dad was part of the Blue Train in Europe. I can’t find anything on it. Yours is the 1st.

I have a picture of your dad with a group called Team I 9th Photo Tech [which later was redesignated as the 16th Photo Tech]. Your dad is third from left. My uncle Delos Erickson is in the picture.

I did talk with my mom. She remembers some things, like how they traveled at night, following the truck ahead of them, without headlights so they would not be seen. She remembered him talking about digging foxholes once they stopped at the next place. Also how scary it was traveling at night and hearing the buzz bombs dropping all around and hoping they would not be hit. … Several years ago, I also looked for information on the Blue Train and 16th Photo Tech unit, but could not find anything. I was really surprised at the lack of records.

The general overview of his time spent in the 16th photo recon unit was that they were always one step ahead of the Germans and that they had to be very careful what they shared with family/friends by way of correspondence, etc.

In response to one question I asked each of these people, I received a few confirmations: “Dad has a bunch of prints of Buchenwald. Pictures that are horrific to look at.” “As for the liberation of the concentration camp, he talked of them finding box cars full of human bones there. I also have some of these photos.”

A well-developed field

I never expected to learn anything specifically about my quiet and reserved father from this research. But this curious military team, of which he was a member, with its unusual task — surely this unit would have some fascinating narrative? But despite the recollections shared by sons-in-law and daughters and nieces of 16th Photo Tech members, ultimately I learned little more about the unit than is in Blue Train, a book frustrating in its incompleteness, since it was written by and for the people who went through the experience together.

Combining almost calligraphy-like handwritten text, stylized illustrations, and documentary photographs, the pages of Blue Train are printed on heavy photographic paper and bound between navy-blue hard covers. The book opens with several pages of squadron history that nearly fetishizes the print production numbers. Next come those headshots, then exterior and interior shots of the film processing trailers, then group shots of the members, then photo collages of places across Europe where the unit worked, and finally reproductions of a few aerial reconnaissance photographs, with the last page featuring what looks like a large, decimated railway depot captioned with, “Bombers did it…reconnaissance proved it.”

One page, titled “Eyes of the Air Force,” provides a paean to the role of military aerial reconnaissance. “Everyone knows it takes millions of men and millions of shells to triumph in modern warfare,” it begins. “But now everyone knows that it also takes millions of pictures.” The next paragraph mentions that reconnaissance “has been credited with supplying 80 to 90 percent of the information obtained by army intelligence.”

Now the province of satellites and unmanned drones, the technology for gathering strategic information from the sky is traced in Unarmed and Unafraid: The First Complete History of the Men, Missions, Training and Techniques of Aerial Reconnaissance, a 1970 book by Glenn B. Infield. The first efforts came during the Civil War, when the Union Army’s attempts to send men up in balloons to report on enemy troop positions were thwarted by telegraph poles and tree limbs. Taking photos from the air had its origins in World War I, through the use of handheld or mounted cameras in planes, although vibrations usually marred the results.

The National Air and Space Museum’s online history of aerial reconnaissance highlights the technological advances created by George Goddard, born in 1889, who shortly after World War I organized the first Army aerial photographic mapping units and essentially invented nighttime aerial reconnaissance. One night in 1925 Goddard showed what he could do by flying over Rochester, New York, igniting a flash powder bomb, and taking a picture of the city startled from its sleep.

In the late 1930s in the village of Medmenham, England, a British Military Intelligence headquarters was secretly established specifically to interpret reconnaissance photos. Winston Churchill’s daughter Sarah served during World War II at Medmenham as an intelligence analyst. In the reconnaissance entry for Military History Online mentioned earlier in the article, author Del Kostka writes, “The strategic value of the intelligence derived through [this office’s] air photo interpretation methods cannot be overstated. In 1940, after the British Expeditionary Force evacuated the continent from Dunkirk and as the Battle of Britain raged, the only option for retaliation left open to the British was RAF air strikes against economic and military targets in German occupied territory.”

Which brings us to the 16th Photo Tech, whose original 58 men and five officers arrived in England in March 1944 and headed to the British military base in Middle Wallop that housed Royal Air Force fighter squadrons and the US 9th Air Force Fighter Command Headquarters.

The unit, with my father, would go on to completely photograph the nearly 400 miles of German forts, tanks, and tunnels known as the Siegfried Line, as the author of Blue Train brags, and apparently play some role in a concentration camp’s liberation, which he doesn’t mention.

Also ahead lay what he really cared about putting down on paper for the men to remember: the 4,457,928 photographic prints they processed along the way.

Theresa Everline is a Philadelphia freelance writer interested in arts, culture, and urban affairs. A former editor-in-chief of Philadelphia City Paper, she has written for the New York Times, the Washington Post's travel section, Next City, Preservation Online, and SmartPlanet.com. Her essay about living in Cairo was selected as a "notable essay" for The Best American Travel Writing 2005.